The first money I ever earned—a big, whoppin’ four dollars, at eight years old, for mowing the neighbor’s gigantic yard—I put into an envelope and mailed to the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, in far off New York City. To this day it seems to me you can get, if not a definitive look, at least a pretty fair appraisal of someone’s heart and humanity by gaining an insight into that person’s regard for and treatment of animals.

I got my first guitar right after turning 17—paid $100, if I recall, earned workin’ construction, for a second-hand 1967 Gibson J-45. After decades playing it, and to perhaps begin a ‘Family Seventeenth Birthday Tradition’, a couple years ago I shipped it off to far away Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. I was passing it on to a boy who’s pretty much my stepson, as he reached 17—south of the Equator, on the shores of the Indian Ocean; the other side of the world. He’s now playing that old flat top in Bangalore, India; returning with it to Africa in a year or so. Ah, where life leads....

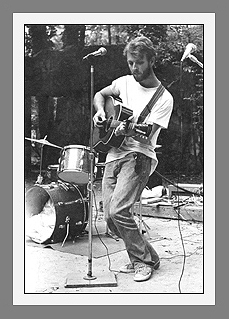

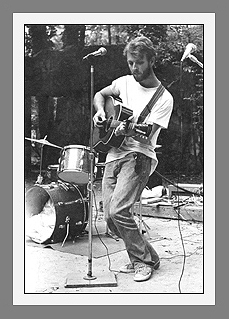

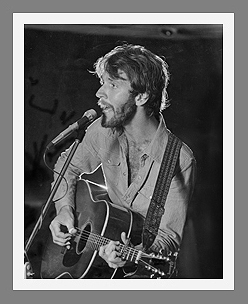

Early gig while hitchiking

through North Carolina

|

Lots of other instruments have come and gone over the years, but ones that have stayed and kinda ‘established a place in the permanent collection’ include a 1961 Gibson Hummingbird, a 1997 Collings D2H, a 1979 Alvarez-Yairi DY-58 nine-string; a 1963 Danelectro Baritone and a 1969 Buck Owens American Guitar, which Buck himself gave me as a present. I usually tune my regular guitars down three half-steps—C# to C#—meaning when I play a ‘G’ chord it’s actually an ‘E’ chord to every other player in the room, causing no end to consternation and exasperation all around. I mostly play Hohner Marine Band harmonicas—along with their (now obsolete and out-of-production) Auto-Valve and Echo harmonicas on occasion. And while this may seem too in-the-weeds—picayune, trivial—to mention, I’m very partial to apparently little-known Golden Gate brand thumb picks. The plastic is much stronger than others out there, so they stay put on your thumb and don’t get worn down nearly as fast as others. (I got turned on to them by Charlie Cox, a long-time pal who’s made an actual living—paying all the bills, doing quite alright, actually—as a street performer; for 30+ years, five-days-a-week, playing out in front of the La Brea Tar Pits Museum down in Los Angeles. [He and I once partnered the entire month after Thanksgiving selling Christmas trees in downtown Manhattan—out on the curb with snow, ice, slush and occasional organized gangs of ‘tree thieves’ pummelling whatever Pleasant Memories I may’ve anticipated one day having.] And, of course, a street performer is the kinda professional who needs stuff to not wear out—so his recommendation was authoritative! Many years later I learned that nonpareil guitarist Tommy Emmanuel also uses Golden Gates, so there you go.)

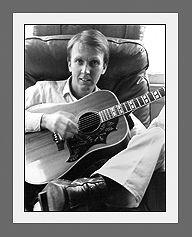

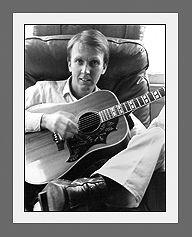

The point of the above paragraph isn’t to hype corporate brands—for instance, despite my appreciation for the Gibsons I’ve mostly played, in my opinion that company hasn’t made a guitar that’s worth crap in around 40 years—but to answer a question or two that’s occasionally asked.Back when the Hummingbird

still had a pickguard

|

I didn’t play anywhere in public for 25 years, from 1976 to 2001, partly because—when I was pretty successfully producing and directing concerts, stage musicals, film projects and television in San Francisco—the pioneering concert promoter Bill Graham advised me (well, severely chastised me is perhaps a more accurate characterization), “You do too many things! You can’t do that!” When I meekly replied, wounded, almost falsetto-voiced, “But all my shows are successful.” He growled back, “Yeah, I know—and you can’t do that! People in this business don’t like it if you do a lot of things—most of ’em can’t even do the one job they have!”

Kinda made sense, actually. So my guitars stayed pretty much out of sight. Even close friends—folks who’d frequently come over for dinner and with whom I’d spend many, many hours through the years socializing and talking about everything else under the sun—didn’t know I owned one, much less played and made up the occasional song. I wasn’t embarrassed, understand, or consciously concealing it from them; just no reason, really, to bring it up.

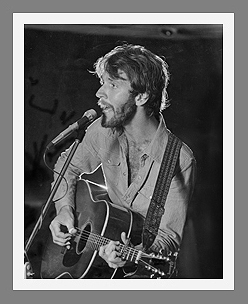

Autumn, 1976: last show before moving

strictly backstage for 25 years

|

It was a chance encounter with an open-mic night at a dive bar called the Hotel Utah in San Francisco—and a lesbian biker barmaid’s bemused persistence—that got me back on stage, that first night (after a few weeks of her coaxing, daring and downright ridiculing my reticence) with “The Yellow Rose of Texas”. I always tried to hassle that Harley-Davidson ridin’ hard-as-nails fun woman as good as she gave—regularly and loudly inquiring as I walked in, “So how’s yer cute little pink Vespa runnin’?”, just to get her snarling and flashing evil eyes back at me.

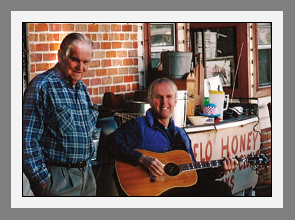

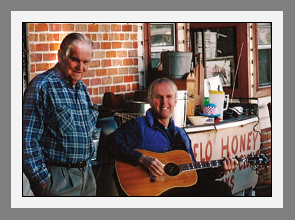

Returning to Ashmore’s Store

|

Culturally, politically, socially, I’m a first-generation American (of German Lutheran and Austrian Catholic immigrant parents), a working class man, and well-aware of how the game is stacked against poor and working people in this world—particularly here in the United States, where willfully moronic right-wing clowns strut and swagger about with their flags, Bibles, impotence-compensating handguns and rapacious self-entitlement. However, in the words that’ll be the refrain line of a song I ain’t yet written but one of these days will, “In the end, conservatives, they always, always—always, always—LOSE”.

I don’t have a television; much prefer bicycling somewhere to driving just about anywhere; read The New Yorker, Harper’s, The Atlantic, The Nation, The New York Review of Books, Film Comment and (despite its utterly insufferable cheerleading for the academic-arts bureaucratic establishment) American Theatre; and use the public library (and interlibrary loan) a whole hell of a lot. I may be that guy you saw at the airport or train station carrying the guitar gig bag, small suitcase—and 10-20 magazine back issues, slowly reading through and discarding them, one after the other, trying to catch up on the danged things.

I regularly walk out of movies 20 minutes or so after they’ve started—or if with a friend, attempt to stoically endure without checking my watch every two minutes. (Keep in mind these are generally free industry screenings; damned if I’m gonna pay $15 for the almost invariably vapid industrial detritus of desperate Hollywood incompetents and indie wannabes.) And—perhaps I shouldn’t divulge this?—rarely listen to other than classical music; the Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque periods generally being my most favored. Yet I treasure silence the most; and always, always have.

Finally, since this is a bio, perhaps a note on some organizations to which I belong is appropriate. Unions are what built the middle class in America—brought about the 8-hour work day and the 40-hour work week, profoundly safer working conditions, paid vacations, maternity leave and sick days, increased productivity, the end of child labor, and a whole lot more that’s good, valuable and just plain morally right. And while I’ve certainly got complaints about each one of ’em to which I myself belong—sometimes big complaints—I’m still very much a proud member of the Director’s Guild of America (DGA); the Stage Directors and Choreographers Society (SDCS); the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE); the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP); and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

Finally, since this is a bio, perhaps a note on some organizations to which I belong is appropriate. Unions are what built the middle class in America—brought about the 8-hour work day and the 40-hour work week, profoundly safer working conditions, paid vacations, maternity leave and sick days, increased productivity, the end of child labor, and a whole lot more that’s good, valuable and just plain morally right. And while I’ve certainly got complaints about each one of ’em to which I myself belong—sometimes big complaints—I’m still very much a proud member of the Director’s Guild of America (DGA); the Stage Directors and Choreographers Society (SDCS); the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE); the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP); and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

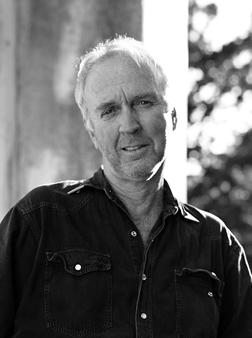

Recently, at home, working on a new song with backup singers Pochiko the Wonderdog and Tama-chan. There’s a cold beer on a small table off to my right. Pochiko the Wonderdog is an alto with a solid belt—especially noticable when the mailman comes by—and Tama is essentially a coloratura mezzo-soprano. This shot may have actually been taken immediately before they launch into their own favorite song—well, most enthusiastically and regularly performed, certainly—called "Hey, Is It Time to Eat Yet?!?"

|

Finally, since this is a bio, perhaps a note on some organizations to which I belong is appropriate. Unions are what built the middle class in America—brought about the 8-hour work day and the 40-hour work week, profoundly safer working conditions, paid vacations, maternity leave and sick days, increased productivity, the end of child labor, and a whole lot more that’s good, valuable and just plain morally right. And while I’ve certainly got complaints about each one of ’em to which I myself belong—sometimes big complaints—I’m still very much a proud member of the Director’s Guild of America (DGA); the Stage Directors and Choreographers Society (SDCS); the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE); the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP); and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

Finally, since this is a bio, perhaps a note on some organizations to which I belong is appropriate. Unions are what built the middle class in America—brought about the 8-hour work day and the 40-hour work week, profoundly safer working conditions, paid vacations, maternity leave and sick days, increased productivity, the end of child labor, and a whole lot more that’s good, valuable and just plain morally right. And while I’ve certainly got complaints about each one of ’em to which I myself belong—sometimes big complaints—I’m still very much a proud member of the Director’s Guild of America (DGA); the Stage Directors and Choreographers Society (SDCS); the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE); the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP); and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).